Biography

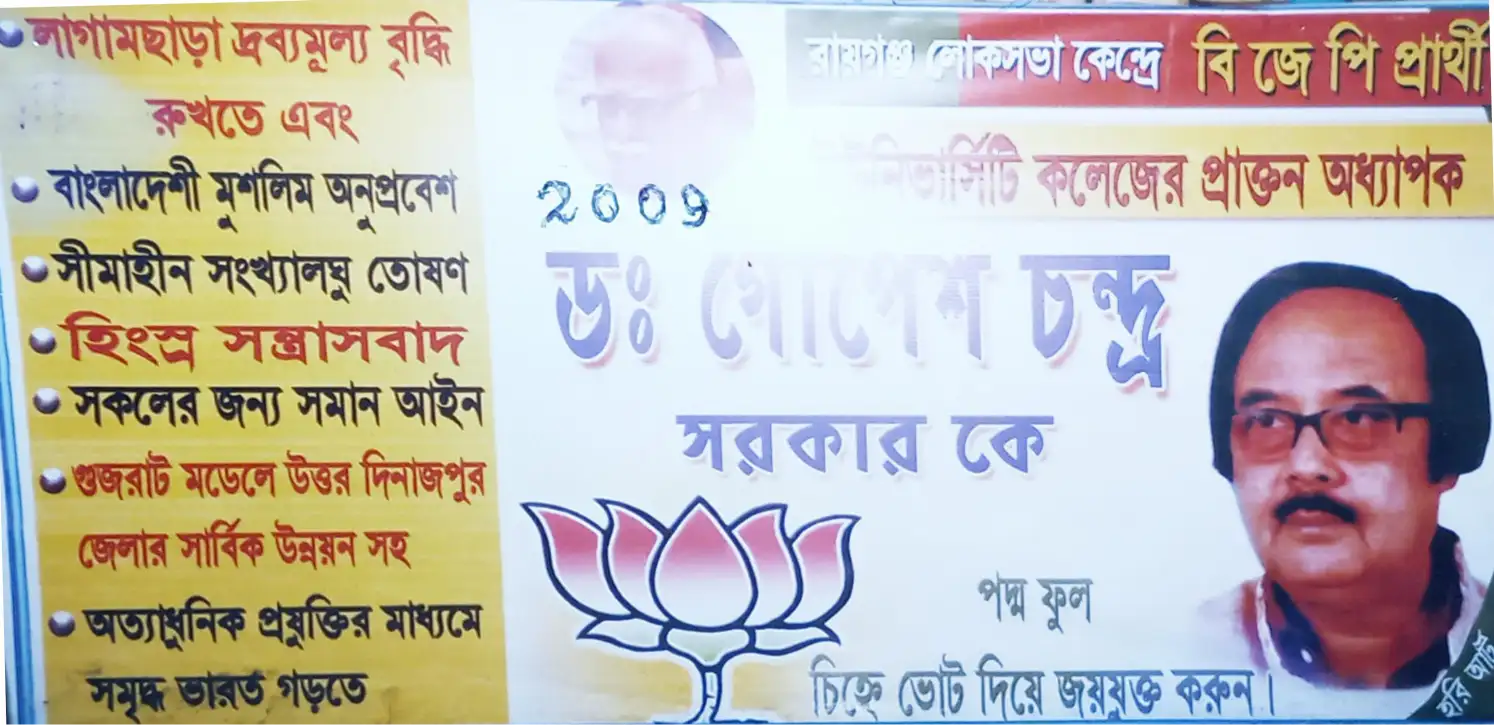

Former RSS President (Sanghachalak) of West Dinajpur District (WB) and Former West Bengal State Vice-President (BJP) and MP candidate for the 2009 Indian General Elections from the Raiganj Constituency.

Former BJP West Bengal State Vice-President

Wikipedia PageA brilliant academic, principled nationalist, and devoted family man, Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar’s life is a testament to resilience, vision, and unwavering dedication. Born in 1941, he carved his path through a newly independent India with relentless discipline and scholarly passion. He earned his Ph.D. in Botany in the 1970s and served as a respected professor until his retirement in 2003, mentoring generations with integrity and quiet strength.

A devoted swayamsevak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and was someone who was invited into the Sangh, he upheld its values of discipline, service, and patriotism throughout his life. In 2009, he fearlessly stepped into politics, contesting as a BJP candidate from Raiganj, not for power, but to champion his ideals—despite limited organizational support or resources.

Alongside his public service, Dr. Sarkar quietly mastered homeopathy, using it only within his family to heal and help—never for fame or fortune. His wisdom and love extended to his family, where he ensured both his sons, Goutam and Uttam, were educated, settled, and supported in their careers and marriages. Even at 80, he made the bold move to buy a home near Kolkata airport—selling his Raiganj property not just for proximity, but to secure his sons’ futures and shield them from legal and political complications.

His story is not just one of milestones, but of meaning. This biography traces the journey of a man who lived not for recognition, but for responsibility, impact, and legacy.

This is the PDF of the A.I generated biography of Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar. This biography is generated using the audio of the orignal 2 hour interview Tuhin Sarkar (grandson) had with Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar to share his wisdom, experiences and remarkable legacy of his life.

This is the audio file of the original 2-hour interview that Tuhin Sarkar (grandson) had with Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar. This interview is in Bengali and it discusses the wisdom, experiences and the legacy of Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar's life.

A Hidden Cultural Legacy: The Wedding Card Modernisation

Before the biography starts, I want to present to you a story of his hidden and rather unknown contribution to the culture of West Bengal. This is the story of a Wedding Card revolution.

Not all legacies are built on fame - some are quietly printed on paper and passed from hand to hand, home to home, over generations.

In the 1970s, during Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar’s own wedding, a subtle gap in tradition stood out. The wedding cards of the time didn’t carry the addresses of the bride or groom’s families. But as a partition-era immigrant from Bangladesh, Dr. Sarkar knew firsthand how scattered families had become. When his wedding card accidentally reunited a long-lost neighbor with her estranged relatives - simply because she saw the bride’s name and recognized the connection - it sparked something in him.

From that day forward, he made it his mission to ensure every wedding card carried full addresses - to help families reconnect, to preserve context, and to create bridges where borders had once created distance.

He took special care to include both family names and proper addresses. This was long before the digital age - when wedding card formats were copied, admired, and reused by families across West Bengal. His thoughtful detail spread through imitation, word-of-mouth, and tradition.

Today, almost every Bengali wedding card carries names and addresses—a small but meaningful trace of a man who believed in connection, and who left behind a legacy most never knew started with him.

A perhaps rather poetic tagline for this story:

“Before the internet connected us, his wedding card did.”

biography:

Chapter 1: Roots Beneath the Floods

Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar was born on the 1st of January, 1941, in a village called Betim, located in what was then the Pabna District of undivided Bengal. It was a time of immense political tension and transition—just six years before India would gain independence from British rule. The subcontinent had not yet been divided, and Bengal was still one.

Despite being officially categorized as a village, Betim was far from undeveloped. The area had a vibrant local economy, supported by a bustling market, agricultural trade, and even a small-scale industry. Temples and schools dotted the region, creating a sense of community and culture that shaped young Gopesh’s early years.

However, nature played a dominating role in village life. Just a few kilometers to the east flowed a mighty distributary of the Brahmaputra River, locally known as the Jamuna. This was not to be confused with the Jamuna of Vrindavan or Delhi. This river had a life of its own—broad, wild, and unforgiving. Every monsoon, it would overflow its banks, engulfing Betim in floods and turning everyday life into a struggle for survival.

To adapt, families in Betim constructed their homes on elevated platforms known as Uju—small artificial mounds that rose above the flood line. Gopesh’s home was one such island in a sea of annual inundation. Nearby lived the Hui family and another locally referred to as the “bus family.” All of them shared the same routine: maintaining boats year-round, ready to be launched as soon as the first waters rose.

Even the journey to school was unconventional. During particularly severe floods, students would ferry one another across water-logged fields. In one such memory, Gopesh recalled being barely a toddler— just a year and a half old—when he was carried to school on the shoulders or heads of older students.

Language, too, was a part of his early challenges. Though surrounded by Bengali speakers, young Gopesh initially spoke little of the local tongue. English education had already found its way into the curriculum under British influence, and he began picking it up early on.

His father, Yogesh Chandra Sarkar, was a respected and successful businessman. The family owned large tracts of fertile land and sustained themselves through agriculture. His mother, Shanti Shudha Sarkar, managed the household with grace and strength. Their lifestyle was relatively comfortable, even during the final years of British colonialism.

In 1947, the partition of India brought a seismic shift in their lives. Pabna, once part of India, became a region of East Pakistan overnight. Gopesh and his family suddenly found themselves as citizens of a different country. In 1971, after the liberation war, East Pakistan transformed into Bangladesh, and the land of Gopesh’s childhood was reborn under a new flag.

Years later, Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar would look back on this period not just as the setting of his early life, but as a foundation that taught resilience, adaptability, and above all, rootedness—values that stayed with him through his journey as a scholar, teacher, and political thinker. He would go on to earn a PhD in the 1970s, but the floods of Betim remained etched into his memory like an origin myth.

Chapter 2: A Scholar Across Borders

The 1950s and '60s were years of upheaval, not just for the Indian subcontinent but for a young man determined to find his place in a fractured world. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar, raised in the floodplains of Betim, had grown up amid both abundance and adversity. But his intellect was never confined by geography. As the political climate in East Pakistan shifted toward religious and cultural suppression of Hindus and Bengali intellectuals, Gopesh knew that his ambitions would need to cross borders.

In the early 1960s, he migrated to India—then a young, chaotic, but hopeful democracy. His arrival marked not just a physical relocation but a transition into a new phase of life: one dedicated to education, knowledge, and service.

He enrolled in college with a focus on Botany, a subject that had long fascinated him since childhood. The green expanses of his homeland had always whispered secrets, and now he sought to uncover them scientifically. Gopesh quickly stood out among his peers—not just for his academic excellence but for his curiosity, eloquence, and deep philosophical nature.

It was during this time that the foundations of his future work began to crystallize. He pursued his M.Sc. in Botany, delving into plant taxonomy, physiology, and ecology with the same dedication that had carried him across a nation’s partition.

But he wasn’t done yet.

In the 1970s, after years of study, fieldwork, and teaching, he earned his PhD in Botany—a rare accomplishment for someone from his background and generation. His doctoral work contributed meaningfully to the understanding of plant systems, especially those endemic to the eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent. Though modest in speaking of his achievements, Gopesh’s academic contributions earned him the title of “Doctor,” and with it, a quiet but powerful respect within his circles.

Even as he focused on his research, his mission was never limited to personal advancement. He began to teach—formally and informally—offering lessons not just in science, but in character. His classrooms were places of deep learning, not rote memorization. He challenged students to ask “why” before accepting “what,” a rare trait in the post-colonial Indian education system.

For Dr. Sarkar, education was liberation. Not just from poverty or ignorance, but from the constraints of fear, prejudice, and narrow thinking. His classroom became an extension of his worldview—secular, rational, and deeply rooted in empathy.

As the 1970s unfolded, the boy who once floated to school on floodwaters had become a man of letters, guiding others through the turbulent waters of knowledge and self-discovery.

Chapter 3: From Scholar to Statesman

The 1950s and '60s were years of upheaval, not just for the Indian subcontinent but for a young man determined to find his place in a fractured world. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar, raised in the floodplains of Betim, had grown up amid both abundance and adversity. But his intellect was never confined by geography. As the political climate in East Pakistan shifted toward religious and cultural suppression of Hindus and Bengali intellectuals, Gopesh knew that his ambitions would need to cross borders.

In the early 1960s, he migrated to India—then a young, chaotic, but hopeful democracy. His arrival marked not just a physical relocation but a transition into a new phase of life: one dedicated to education, knowledge, and service.

He enrolled in college with a focus on Botany, a subject that had long fascinated him since childhood. The green expanses of his homeland had always whispered secrets, and now he sought to uncover them scientifically. Gopesh quickly stood out among his peers—not just for his academic excellence but for his curiosity, eloquence, and deep philosophical nature.

It was during this time that the foundations of his future work began to crystallize. He pursued his M.Sc. in Botany, delving into plant taxonomy, physiology, and ecology with the same dedication that had carried him across a nation’s partition.

But he wasn’t done yet.

In the 1970s, after years of study, fieldwork, and teaching, he earned his PhD in Botany—a rare accomplishment for someone from his background and generation. His doctoral work contributed meaningfully to the understanding of plant systems, especially those endemic to the eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent. Though modest in speaking of his achievements, Gopesh’s academic contributions earned him the title of “Doctor,” and with it, a quiet but powerful respect within his circles.

Even as he focused on his research, his mission was never limited to personal advancement. He began to teach—formally and informally—offering lessons not just in science, but in character. His classrooms were places of deep learning, not rote memorization. He challenged students to ask “why” before accepting “what,” a rare trait in the post-colonial Indian education system.

For Dr. Sarkar, education was liberation. Not just from poverty or ignorance, but from the constraints of fear, prejudice, and narrow thinking. His classroom became an extension of his worldview—secular, rational, and deeply rooted in empathy.

As the 1970s unfolded, the boy who once floated to school on floodwaters had become a man of letters, guiding others through the turbulent waters of knowledge and self-discovery.

Chapter 4: The Healer Within

The 1950s and '60s were years of upheaval, not just for the Indian subcontinent but for a young man determined to find his place in a fractured world. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar, raised in the floodplains of Betim, had grown up amid both abundance and adversity. But his intellect was never confined by geography. As the political climate in East Pakistan shifted toward religious and cultural suppression of Hindus and Bengali intellectuals, Gopesh knew that his ambitions would need to cross borders.

In the early 1960s, he migrated to India—then a young, chaotic, but hopeful democracy. His arrival marked not just a physical relocation but a transition into a new phase of life: one dedicated to education, knowledge, and service.

He enrolled in college with a focus on Botany, a subject that had long fascinated him since childhood. The green expanses of his homeland had always whispered secrets, and now he sought to uncover them scientifically. Gopesh quickly stood out among his peers—not just for his academic excellence but for his curiosity, eloquence, and deep philosophical nature.

It was during this time that the foundations of his future work began to crystallize. He pursued his M.Sc. in Botany, delving into plant taxonomy, physiology, and ecology with the same dedication that had carried him across a nation’s partition.

But he wasn’t done yet.

In the 1970s, after years of study, fieldwork, and teaching, he earned his PhD in Botany—a rare accomplishment for someone from his background and generation. His doctoral work contributed meaningfully to the understanding of plant systems, especially those endemic to the eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent. Though modest in speaking of his achievements, Gopesh’s academic contributions earned him the title of “Doctor,” and with it, a quiet but powerful respect within his circles.

Even as he focused on his research, his mission was never limited to personal advancement. He began to teach—formally and informally—offering lessons not just in science, but in character. His classrooms were places of deep learning, not rote memorization. He challenged students to ask “why” before accepting “what,” a rare trait in the post-colonial Indian education system.

For Dr. Sarkar, education was liberation. Not just from poverty or ignorance, but from the constraints of fear, prejudice, and narrow thinking. His classroom became an extension of his worldview—secular, rational, and deeply rooted in empathy.

As the 1970s unfolded, the boy who once floated to school on floodwaters had become a man of letters, guiding others through the turbulent waters of knowledge and self-discovery.

Chapter 5: Roots and Responsibility

Beyond the classroom, the laboratory, and even the quiet pages of his homeopathic journals, Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar was, at his core, a deeply devoted family man. His life was not defined solely by academic accolades or intellectual exploration. It was anchored by responsibility, love, and values passed down through generations.

Born in 1941, he grew up in a time when the meaning of "family" extended beyond the nuclear structure. Kinship meant duty, sacrifice, and unwavering support—principles he carried with him through every stage of his life. Even as he pursued higher education and built a scholarly reputation, he never saw personal success as separate from the well-being of his family.

He married in the early years of his career, forming a household that would become a place of both learning and warmth. His relationship with his wife was one of mutual respect, quiet understanding, and shared resilience. Together, they raised children with values rooted in honesty, discipline, and education. While he was not overtly strict, there was an unspoken structure in the home—a rhythm guided by his own lifestyle: measured, thoughtful, and always purposeful.

Dr. Sarkar believed that education began at home. Books lined the shelves of his residence, and discussions at the dinner table often drifted toward ideas rather than gossip. He never imposed his views, but led by example. It wasn’t unusual for his children to see him immersed in reading at odd hours or quietly working on lesson plans long after retiring from formal service.

Yet, for all his intellect, he was a man of simplicity. He disliked extravagance, preferring moderation in both material life and speech. His clothes were modest, his habits disciplined, and his desires minimal. If he held any pride, it was in the accomplishments of those he loved.

His relationship with his grandchildren added a new dimension to his life. No longer bound by the pressures of work, he took joy in their questions, their quirks, and their curiosity. He never imposed expectations on them, but gently nudged them toward self-belief and integrity. His interactions were never theatrical, but they lingered in memory—a quiet story, a relevant quote, a small act of encouragement.

Behind his quiet demeanor was a deep well of emotion. He felt pain deeply, though he seldom expressed it. He had endured loss, political disillusionment, health struggles—but his resilience remained intact, shaped by decades of discipline and an unshakable inner compass.

To him, life was not about chasing recognition, but about fulfilling one's dharma—one's duty. Whether it was to his students, his children, or even to himself, he believed in showing up, doing the work, and letting the results follow.

In a world increasingly drawn to speed, noise, and visibility, Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar lived a life of quiet substance. His was not the legacy of a public icon, but of a rooted elder whose presence gave

strength to those around him—not through grand gestures, but through steady love, earned wisdom, and unwavering responsibility.

Chapter 6: The Reluctant Politician

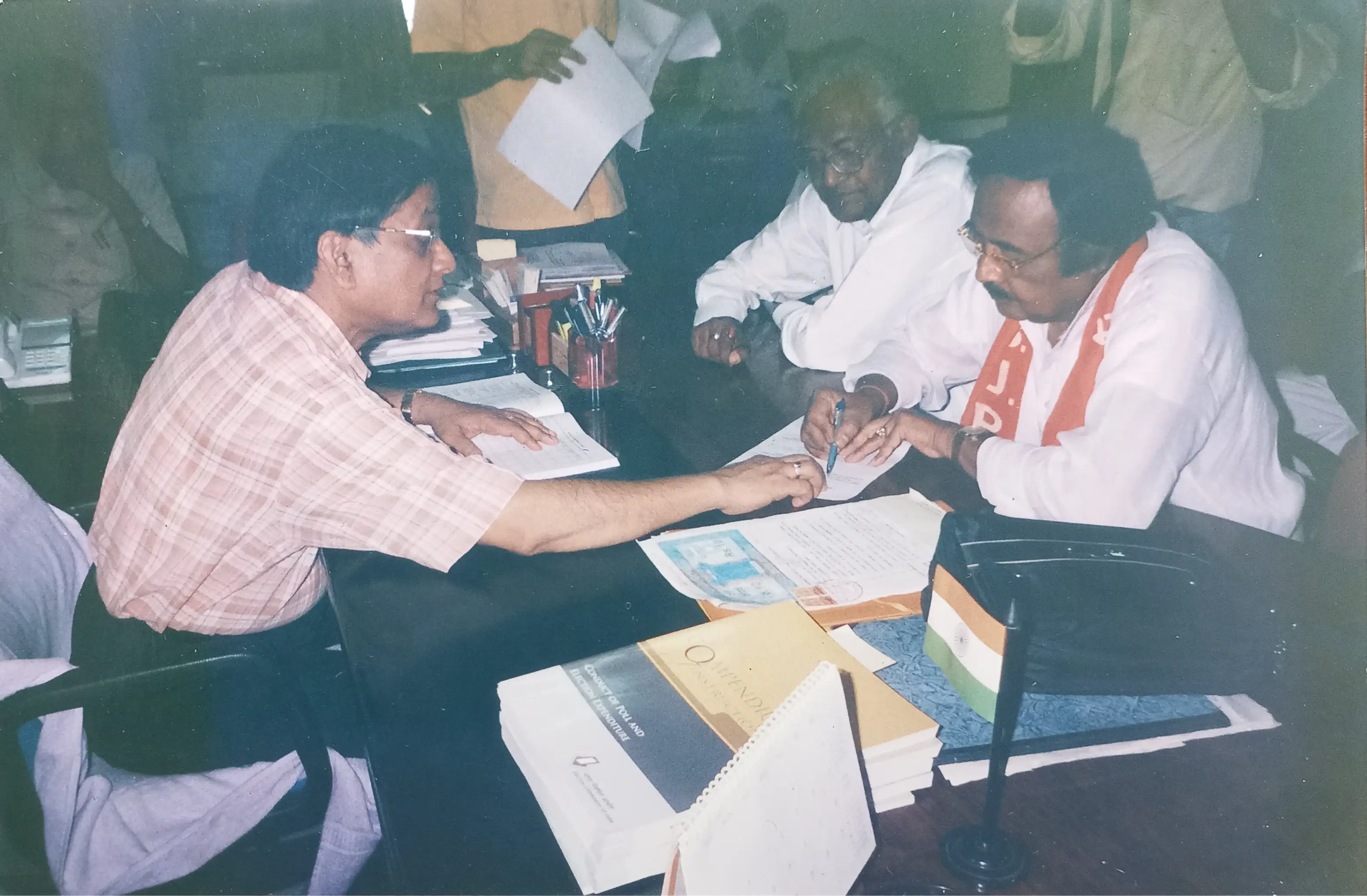

In 2009, long after his retirement and well into his years of reflection and quiet living, Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar made a decision that surprised many: he entered the political arena.

At the age of 69, he stood as a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) candidate in the Indian General Elections from the Raiganj Lok Sabha constituency in West Bengal. For someone who had spent most of his life in the contemplative worlds of academia and personal healing, this foray into public service was neither an ambition nor a sudden leap. It was, as with most things in his life, an act of principle.

Dr. Sarkar had long observed the decay of values in Indian politics. The corruption, the opportunism, and the lack of ideological substance disheartened him. He believed that politics should serve the people—not exploit them. It wasn’t about power, but responsibility. And so, when the opportunity arose to represent a party whose core nationalist ideals he resonated with, he accepted—not out of personal desire, but out of a sense of duty to his country and his region.

He campaigned not with flashy promises or large rallies, but with ideas. He spoke to people directly, often walking from home to home, engaging them with sincerity. His tone was never confrontational—he was not a crowd-pleaser—but he offered clarity. He spoke about educational reforms, rural development, and integrity in governance. Many listened. Some dismissed him. A few were inspired.

In a political landscape dominated by seasoned campaigners and party loyalists, Dr. Sarkar’s honest, academic demeanor stood out. He had no interest in political theatrics. He refused to make false promises or participate in mudslinging. He carried with him a scholar’s mind, a teacher’s clarity, and a citizen’s earnest hope.

Ultimately, he received 40,000 votes, a commendable number for a first-time candidate in a stronghold dominated by Congress leader Deepa Dasmunsi, who won the seat with over 450,000 votes. Dr. Sarkar did not take the defeat personally. He never expected to win. His candidacy had not been about victory— it had been about making a point. About showing that good people, even if unelectable, must still try.

After the election, he quietly stepped away from politics, returning to the peace of his home, his books, and his family. He never expressed regret. In fact, he would often say, “At least I tried. At least I did not sit on the sidelines and complain.”

His brief political chapter was not defined by fame, headlines, or influence—but by courage, conviction, and clarity of conscience. In a time when many intellectuals stayed distant from politics out of cynicism or fear, Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar walked into it, knowing full well what it entailed, and emerged with his integrity untouched.

Chapter 7: The Silent Legacy

In 2009, long after his retirement and well into his years of reflection and quiet living, Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar made a decision that surprised many: he entered the political arena.

At the age of 69, he stood as a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) candidate in the Indian General Elections from the Raiganj Lok Sabha constituency in West Bengal. For someone who had spent most of his life in the contemplative worlds of academia and personal healing, this foray into public service was neither an ambition nor a sudden leap. It was, as with most things in his life, an act of principle.

Dr. Sarkar had long observed the decay of values in Indian politics. The corruption, the opportunism, and the lack of ideological substance disheartened him. He believed that politics should serve the people—not exploit them. It wasn’t about power, but responsibility. And so, when the opportunity arose to represent a party whose core nationalist ideals he resonated with, he accepted—not out of personal desire, but out of a sense of duty to his country and his region.

He campaigned not with flashy promises or large rallies, but with ideas. He spoke to people directly, often walking from home to home, engaging them with sincerity. His tone was never confrontational—he was not a crowd-pleaser—but he offered clarity. He spoke about educational reforms, rural development, and integrity in governance. Many listened. Some dismissed him. A few were inspired.

In a political landscape dominated by seasoned campaigners and party loyalists, Dr. Sarkar’s honest, academic demeanor stood out. He had no interest in political theatrics. He refused to make false promises or participate in mudslinging. He carried with him a scholar’s mind, a teacher’s clarity, and a citizen’s earnest hope.

Ultimately, he received 40,000 votes, a commendable number for a first-time candidate in a stronghold dominated by Congress leader Deepa Dasmunsi, who won the seat with over 450,000 votes. Dr. Sarkar did not take the defeat personally. He never expected to win. His candidacy had not been about victory— it had been about making a point. About showing that good people, even if unelectable, must still try.

After the election, he quietly stepped away from politics, returning to the peace of his home, his books, and his family. He never expressed regret. In fact, he would often say, “At least I tried. At least I did not sit on the sidelines and complain.”

His brief political chapter was not defined by fame, headlines, or influence—but by courage, conviction, and clarity of conscience. In a time when many intellectuals stayed distant from politics out of cynicism or fear, Dr. Gopesh Chandra Sarkar walked into it, knowing full well what it entailed, and emerged with his integrity untouched.

.png)